Straw men and live horses...

|

| Giant straw men are still just straw men! |

If you ask me ‘What are you?’ I would probably be a

something of a loss, at least for a moment, while I assess the context and

seriousness of your question. Maybe you are mocking me or criticizing or satirizing

some aspect, trivial or central, of my behaviour. My response is likely to differ

depending in large measure on the degree of self-knowledge I have. If I am a

rogue trader who is covering up a massive fraud of my employer’s assets – like

the ‘master fraudster, Kweku Adoboli, who

misappropriated £1.4 billion of the Swiss bank’s assets – I am likely to think

first of that circumstance rather than of anything other. If, again, to take

another example, you were a border guard at the Turkish-Iraq border and are

examining my passport, then I would have some clearer sense of your concern and

I would struggle to reassure you that I was an innocent British traveller

researching likely locations in the Kurdish mountains for a new James Bond

film. True, you as a conscientious border guard might not be very convinced or

willing to let me go without a good deal of further questioning.

But if there

is no obvious circumstance that as far as I can see you may be referring to - when

as is normally the case it seems unlikely that you should have any access to my

secret stores of guilt and transgression - then I might look a little

quizzically at you, as if to ask what you might intend by asking such a vacuous

question. If then you went on to explain that you wanted to ask if I were ‘a type

of entity such that both predicates ascribing states of consciousness and

predicates ascribing corporeal characteristics ... [were] equally applicable to

a single individual of that type’ such as I myself might be taken to be, I - and

also I think you - would be likely to laugh at this unprovoked absurdity. This of course was Strawson's way of putting the question as quoted at the beginning of Frankfurt's article. For may people this kind of tough, objective approach is what philosophy is all about. Frankfurt did not entirely agree with this and much more strongly Kierkegaard was totally opposed to this way of thinking, which he mocked as belonging to the world of assistant professors.

|

| A graminivorous quadruped? |

It may be true that I am such an

entity, one that attracts two opposed kinds of predicates. It may also be true, as Harry Frankfurt points out, that there are logical

difficulties with this description, but these difficulties are not the

immediate or principal source of our discomfort. We would feel, more simply,

that this supposed definition of our personhood – our humanity – had simply

missed the point, like a broad-scale mesh that lets even the biggest fish

through the net. It is knowledge that is irrelevant to the business of our

lives as we live them from hour to hour and year to year. It

has no more relevance than Bitzer’s definition of a horse: ‘Quadruped.

Graminivorous. Forty teeth, namely twenty-four grinders, four eye-teeth, and

twelve incisive. Sheds coat in the spring; in marshy countries, sheds hoofs

too. Hoofs hard but requiring to be shod with iron. Age known by marks in mouth’.

Young Bitzer, faithful to the teaching of Mr Gradgrind, clearly knows all about

horses, or does at least for the purposes of surviving in Gradgrind’s

classroom.(Charles Dickens, Hard Times,

1854). This is another broad-scale mesh that fails to capture the life and

liveliness of horses of the kind that Sissy Jupe knew in the colours of her

father’s circus-tent. Poor Sissy had no chance when faced with this man who was

like a cannon loaded to the muzzle with facts aimed at ‘the tender imaginations

of childhood’.

|

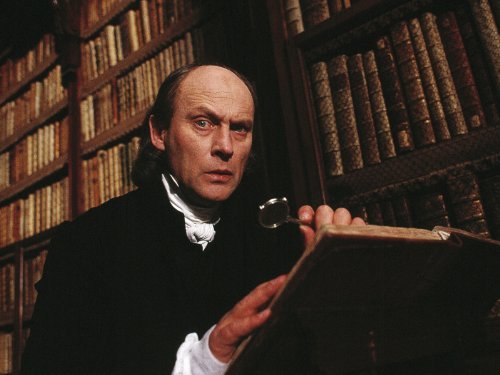

| Poor Casaubon, poor Dorothea, poor us! |

Knowledge of this kind is dead. It has no relevance to the embedded

warp of our lives. Edward Casaubon in George Eliot’s Middlemarch is this kind of horror story writ large. His great work, The Key to All Mythologies, turns out

to be as desiccated and divorced from life as the man himself. The pursuit of knowledge,

of dead academic accumulation, takes his life into the desert. Instead of living

his life, he chose to do something else instead. His young wife, Dorothea Brooke, also comes to

see the foolishness of trying to find fulfilment by sharing in her husband’s intellectual

work rather than in trying to live a life that is more truly her own. But her

knowledge is something very different because it is the slow realization that

something is very wrong. It is a

realization that will save her even if it brings adverse judgement and social

exclusion.

We see something broadly similar in the picture of the final days of

Ivan Illych in Tolstoy’s short story. Ivan’s seemingly trivial fall from a

ladder when putting up new curtains brings increasing pain and makes him reflect

on the semi-automatic life he had lived devoted to work as an escape from a

loveless marriage. The true character of this life becomes apparent in the

shadow of his approaching death. He comes to see his old life as artificial,

lacking the sympathy and compassion that he now sees as the character of

authentic existence. Dorothea and Ivan come to see how they should live and

this for them is knowledge of a very different kind. This new kind of knowledge

is knowledge about how to live and not the sort of detached theoretical

knowledge that you can put into your pocket or mug up for examinations. It is knowledge that shapes the present hour as we come to it, not knowledge that you can put directly into a textbook.

|

| Yasnaya Polyana or 'Bright Glade,' where Tolstoy wrote and was buried. |

I hadn’t intended to make this excursion but it has some

relevance to our story. Harry Frankfurt’s account of what we should understand

by the concept of a person is still an objective account but it is much closer

to the pulse of human life than Strawson’s definition which arguably can never

tell us anything that might help us to live and love our lives. This makes

Frankfurt’s account much more interesting and much more relevant to our reading

of Kierkegaard for Kierkegaard looks at a life and examines every aspect of it

in dramatic and novelistic ways. Frankfurt looks only at the human will as

something that points toward everything that is ‘important and problematical in

our lives’. The pictures of the three addicts that he gives us may be seen as a

summary of much of what he has to say. That is what I will try to present in a few paragraphs in the next post.

No comments:

Post a Comment