Struggling to be free?

|

| OSEZ ETRE QUI VOUS ESTES…OSEZ LA LIBERTE!

|

III

«There is a very close relationship between the capacity for

forming second-order volitions and another capacity that is essential to

persons - one that has often been considered a distinguishing mark of the human

condition. It is only because a person has volitions of the second-order that

he is capable both of enjoying and lacking freedom of the will. The concept of

a person, then, is not only the concept of a type of entity that has both

first-order desires and volitions of the second order. It can also be construed

as the concept of a type of entity for whom the freedom of its will may be a problem.

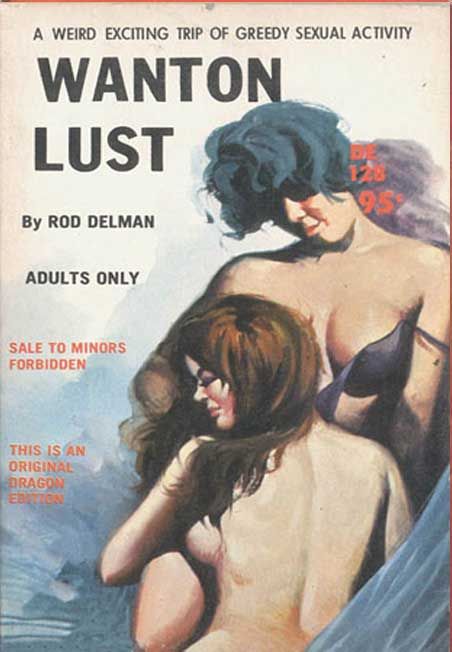

This concept excludes all wantons, both infrahuman and human, since they fail

to satisfy an essential condition for the enjoyment of freedom of the will. And

it excludes those suprahuman beings, if any, whose wills are necessarily free.

«Just what kind of freedom is the freedom of the will? This

question calls for an investigation of the special area of human experience to

which the concept of the freedom of the will, as distinct from the concepts of

other sorts of freedom, is particularly germane. In dealing with it, my aim

will be primarily to locate the problem with which a person is most immediately

concerned when he is concerned with the freedom of the will.

«According to one familiar psychological tradition, being

free is fundamentally a matter of doing what one wants to do. Now the notion of

an agent who does what he wants to do is by no means an altogether clear one:

both the doing and the wanting, and the appropriate relation between them as

well, require elucidation. But although its focus needs to be sharpened and its

formulation refined, I believe that this notion does capture at least part is

implicit in the idea of an agent who acts

freely. It misses entirely, however, the peculiar content of the quite

different idea of an agent whose will

is free.

«We do not suppose that animals enjoy freedom of the will,

although we recognize that an animal may be free to run i whatever direction it

wants. Thus, having the freedom to do what one wants to do is not a sufficient

condition of having a free will. It is not a necessary condition either. For to

deprive someone of his freedom of action is not necessarily to undermine the

freedom of his will. When an agent is aware that there are certain things he is

not free to do, this doubtless affects his desires and limits the range of

choices he can make. But suppose that someone, without being aware of it, has i

fact lost or been deprived of his freedom of action. Even though he is no

longer free to do what he wants to do, his will may remain as free as it was

before. Despite the fact that he is not free to translate his desires into

actions or to act according to the determinations of his will, he may still

form those desires and make those determinations as freely as if his freedom of

action had not been impaired.

«When we ask whether a person’s will is free we are not

asking whether he is in a position to translate his first-order desires into

actions. That is the question of whether he is free to do as he pleases. The

question of the freedom of his will does not concern the relation between what

he does ad what he wants to do. Rather, it concerns his desires themselves. But

what question about them is it?

«It seems to me both natural and useful to construe the

question of whether a person’s will is free in close analogy to the question of

whether an agent enjoys freedom of action. Now freedom of action is (roughly at

least) the freedom to do what one wants to do. Analogously, then, the statement

that a person enjoys freedom of the will means (also roughly) that he is free

to want what he wants to want. More precisely, it means that he is free to will

what he wants to will, or to have the will he wants. Just as the question about

the freedom of an agent’s action has to do with whether it is the action he

wants to perform, so the question about the freedom of his will has to do with

whether it is the will he wants to have.

«It is in securing the conformity of his will to his

second-order volitions, then, that a person exercises freedom of the will. And

it is in the discrepancy between his will and his second-order volitions, or i

his awareness that their coincidence is not his own doing but only a happy

chance that a person who does have this freedom feels its lack. The unwilling

addict’s will is not free. This is shown by the fact that it is not the will he

wants. It is also true, though in a different way, that the will of the wanton

addict is not free. The wanton addict neither has the will he wants nor has a will

that differs from the will he wants. Since he has no volitions of the second-order,

the freedom of his will cannot be a problem for him. He lacks it, so to speak,

by default.

«People are generally far more complicated than my sketchy

account of the structure of a person’s will may suggest. There is as much

opportunity for ambivalence, conflict and self-deception with regard to desires

of the second order, for example, as there is with regard to first-order

desires. If there is an unresolved conflict among someone’s second-order

desires, then he is in danger of having no second-order volition; for unless

this conflict is resolved, he has no preference concerning which of his

first-order desires is to be his will. This condition, if it is so severe that

it prevents him from identifying himself in a sufficiently decisive way with

any of his conflicting first-order desires, destroys him as a person. For it

either tends to paralyze his will and to keep him from acting at all, or it

tends to remove him from his will so that his will operates without his

participation. In both cases he becomes, like the unwilling addict though in a

different way, a helpless bystander to the forces that move him.

«Another complexity is

that a person may have, especially if his second-order desires are in conflict,

desires and volitions of a higher order than the second. There is no

theoretical limit to the length of the series of desires of higher and higher

orders,; nothing except common sense and, perhaps, a saving fatigue prevents an

individual from obsessively refusing to identify himself with any of his

desires until he forms a desire of the next higher order. The tendency to

generate such a series of acts of forming desires, which would be a case of humanization

run wild, also leads towards the destruction of a person.

«It is possible, however, to terminate such a series of acts

without cutting it off arbitrarily. When a person identifies himself decisively

with one of his first-order desires, this commitment ”resounds” throughout the

potentially endless array of higher orders. Consider a person who, without

reservation or conflict, wants to be motivated by a desire to concentrate on

his work. The fact that his second-order volition to be moved by this desire is

a decisive one means that there is no room for questions concerning the

pertinence of desires or volitions of higher orders. Suppose the person is asked

whether he wants to want to want to concentrate on his work. He can properly

insist that this question concerning a third-order desire does not arise. It

would be a mistake to claim that because he has not considered whether he wants

the second-order volition that he has formed, he is indifferent to the question

of whether it is with this volition or with some other that he wants his will

to accord. The decisiveness of the commitment he has made means that he has

decided that no further questions about his second-order volition, at any

higher order, remains to be asked. It is relatively unimportant whether we

explain this by saying that this commitment implicitly generates an endless

series of confirming desires of higher orders, or by saying that the commitment

is tantamount to a dissolution of the pointedness of all questions concerning

higher order s of desires.

«Examples such as the one concerning the unwilling addict may

suggest that volitions of the second order, or of higher orders, must be formed

deliberately and that a person characteristically struggles to ensure that they

are satisfied. But the conformity of a person’s will to his higher order

volitions may be far more thoughtless and spontaneous than this. Some people

are naturally moved by kindness when they want to be kind, and by nastiness

when they want to be nasty, without any explicit forethought and without any need

for energetic self-control. Others are moved by nastiness when they want to be

kind and by kindness when they intend to be nasty, equally without forethought

and without active resistance to these volitions of their higher-order desires.

The enjoyment of freedom comes easily to some. Others must struggle to achieve

it.»

Footnote: The picture is of a sculpture by Zenos Frudakis. It stands outside the GlaxoSmithKline Headquarters in Philadelphia. The artist's message is clear, though it is not clear what part drugs play in that freedom!