We talked about Montaigne...

Montaigne's message is by and large strikingly secular in its accents. He seems to be dealing with himself and others in an entirely material world, but this statement seems to go beyond this in an interesting way. For all our ordinary hesitations and hang-ups, our regrets and our attempts at reform, he seems to advocate a sort of wise acceptance of oneself and the limitations of our nature, but we see here that he does accept - even if only glancingly - the more radical possibility of a genuine repentance, something much closer to Christian repentance or metanoia, which reflects the underlying Hebrew concept of teshuvah, which means 'return'. It is an entirely orthodox view that he expresses here. We cannot reform ourselves as though we were engineers of our own natures. For that we need the sort of quality or power that comes from outside ourselves. In traditional theological terms this is the grace or divine gift or favour that comes from God. The opposite view in the theological tradition is what used to be called pelagianism, after the British ascetic Pelagius, whose views were eventually branded as heretical by Augustine at the Council of Carthage. Pelagius thought that you could shape and improve yourself - 'pull your own strings' as they say in California. Augustine took the view that we needed help from outside or above ourselves if we were to have any chance of success in this endeavour.

Two very different views of ethics can be seen here. There is the sergeant-major-cum-schoolmaster view that you can drill and beat people towards perfection and the view that we are not free to become what we ought or want to become and that the power must come from outside ourselves. I think that most of us would want to say that we need something of both these attitudes. We have a certain responsibility for ourselves and can hardly in human terms at least expect to be helped before we have made some attempt to get up on our own feet and that would surely demand a certain amount of habituation, of being brought up in the right way. On the other hand the idea that we can achieve everything by ourselves, as though as each of us were his own Michelangelo, carving beautiful marble versions of ourselves, seems to belie the limitations that we know are ours. Some things are just given, like the gracefulness of a gazelle, and, for Augustine, the gratia or grace of God.

One of the features of modern ethical theory has been a belief that everything can be achieved through human volition and by having the right intellectual view of the world, but as we know that kind of view soon leads to the blind alleys of the police state. The Catholic Church has certainly no better record than the worst of the Jacobins and their modern successors. We need only to think of the Churches behaviour in Spain during the Civil War, but then maybe that was because they too thought that they had all that was necessary for a complete answer to the world's problems, that they had the answer in their hands, like Dostoevsky’s Grand Inquisitor. And Montaigne? Where does he stand in all this? Well, he seems to be almost exclusively concerned with our limitations and contingency and how to come to come to terms with them, and underlying this view, perhaps, is the orthodox Christian view that real reform can only come from outside. As he says at some length in Of experience, you don’t get justice by just making more and more laws. The ingenuity of human reason alone won't get us there, but he isn’t either, as far as I can see, advocating a doctrine of sola fide – the idea that we can be justified in a religious sense by faith alone - much less the enthusiasm of antinomianism. Montaigne isn’t rejecting reason, but he is keenly aware of its imperfect and often self-serving nature. Instead he gently urges an acceptance of our limitations, that’s to say, an acceptance of our contingent nature.

Let me make one last - well, penultimate - observation which perhaps points to a very opposite conclusion. In his essay On cannibals, Montaigne describes the nations of the new world of what was then called New France and which today we know as Brazil:

One last point: - Is Montaigne philosophy? I think it is, though it is certainly not an academic treatise like those that university academics started to grind out first in late-eighteenth century Germany and then in every other European country. If today we think that philosophy must always be in the shape of abstruse articles or intractable academic treatises maybe we ought to lay the blame at the feet of Immanuel Kant and the university system of the Prussian state. Philosophy wasn't always like that. Plato's essays are highly wrought works of literary art and reflect the changing currents of his thought. The journey was the thinking and the thinking was in good measure (though of course not entirely) about the nature, and how we might attain, good judgment - sophrosune - or as the word ‘philosophy’ itself indicates, the pursuit or love of wisdom, but, as we know, one can chase and chase wisdom but somehow she always seems to get away! Montaigne shows us something about how all this works out in the messy business of living the lives that are given to us.

We talked the other day about Montaigne, the man Nietzsche thought an ornament to human life, someone who has increased the pleasure of existing in this world. What did Nietzsche mean, or at least, what might he have meant? I imagine that he had in mind the sense we have of Montaigne as a man who has gracefully resolved the problems of living a life that was heir, as all our lives are, to all of life's intrinsic troubles. He hopes to be able to accept himself with such features and faults as he has and not to put himself on the rack of perfection.

Henri IV, the French king who was stabbed to death by a Catholic fundamentalist 400 years ago. Montaigne acted as a diplomat for Henri de Navarre, who later became Henri IV. Henry IV is credited with ending the wars between Catholics and Protestants. Following the St Bartholomew's Day massacre of Protestants, he was forced to convert to Catholicism, allegedly declaring, "Paris is worth a Mass". Despite his popularity, Henri IV was assassinated on May 14, 1610, by a Catholic fanatic Francois Ravaillac. His embalmed body was buried in the basilica of Saint-Denis, north of Paris. In 1793, however, revolutionaries dug up the body and chopped off his embalmed head..

This is a portrait of an Indian Chief in the territory that became Virginia. It was painted by John White in about 1575. It is therefore nearly contemporary with Montaigne and Shakespeare. Montaigne's On Cannibals shows us a picture of the Indian societies in what is today called Brazil, but which was then New France. Montaigne went to great trouble to meet and to get to know some of the Indians who had been brought to France.The picture he gives us of naturally virtuous people was no doubt sincere but it was probably also motivated by a desire to contrast their virtuous simplicity with the treachery of French political life and society at that time.

We might feel discontented with ourselves but repentance is probably not going to change our basic characteristics. Often we don't really mean or think in terms of genuine repentance. We think instead about the regrets we have for things we've said or done, gauche or unfeeling remarks or acts of pettiness in any of their many varieties, but regrets don't really change our lives; at best, they may put us on notice to be a little more circumspect before opening our mouths or slower in acting. We know that the inner engine that produces these erratic acts is unlikely to be changes by these attempts at regrets. We might, prompted by some more serious situation, we might feel moved to attempt some personal reforms; we tell ourselves that we will try to be braver in admitting our errors, faults and shortcomings or less lazy and evasive, less lecherous or plain greedy; in all of these projects no doubt the first true step is recognizing that this is what we are like and that this is what we have in fact done on this and that occasion, but even these programmes tend to have only marginally successful results. Instead of genuine reform, we often settle for the enjoyable luxury of admitting the truth, at least to ourselves, but then find it easy to forget as one day dies and another arrives. The inner man has no more success in changing himself than the outer woman has with her diets - and vice versa! We remain basically the same person, though perhaps a little wiser about ourselves through many years of self-reminding.

We might feel discontented with ourselves but repentance is probably not going to change our basic characteristics. Often we don't really mean or think in terms of genuine repentance. We think instead about the regrets we have for things we've said or done, gauche or unfeeling remarks or acts of pettiness in any of their many varieties, but regrets don't really change our lives; at best, they may put us on notice to be a little more circumspect before opening our mouths or slower in acting. We know that the inner engine that produces these erratic acts is unlikely to be changes by these attempts at regrets. We might, prompted by some more serious situation, we might feel moved to attempt some personal reforms; we tell ourselves that we will try to be braver in admitting our errors, faults and shortcomings or less lazy and evasive, less lecherous or plain greedy; in all of these projects no doubt the first true step is recognizing that this is what we are like and that this is what we have in fact done on this and that occasion, but even these programmes tend to have only marginally successful results. Instead of genuine reform, we often settle for the enjoyable luxury of admitting the truth, at least to ourselves, but then find it easy to forget as one day dies and another arrives. The inner man has no more success in changing himself than the outer woman has with her diets - and vice versa! We remain basically the same person, though perhaps a little wiser about ourselves through many years of self-reminding.

How does Montaigne solve these enduring problems of our life? I think the answer is - bluntly and crudely speaking - by recognizing these truths about himself, acknowledging his greed at table and other failings, and increasing a little in self-knowledge at least to the extent of acknowledging just how much we are creatures of our impulses and unchosen environment. The German who believes so strongly in the singular effectiveness of German stoves is matched by the Frenchman’s preference for open fires and high beds with curtains. Our first task is to get a handle on our sheer contingency. That's just how we are, products of habits and unpoliced impulses and unacknowledged cultural inheritances. We should no more try to take arms against these facts of our natures than we should refuse to give to our bodily exigencies the time and attention that they demand. (You will recall Montaigne's mention of the Aesop's story about the busy master who was in such a hurry that he just pissed himself as he walked!) Life is in at least some measure learning to make accommodation with our factual selves. The more gracefully we can accept these things the less likely we would be to get fancy opinions about our capacity for high-flown theoretical judgements or to indulge in notions about being wise or having an elevated status. We wouldn't then be so ready to judge the world as though we enjoyed the superior vantage point of a man on stilts nor would we be so quick to forget that every king makes contact with his throne with his behind. His essay On experience reminds us indirectly that we are vulnerable embodied creatures. We might aspire to wisdom but for the most part that is as far as we get.

Montaigne's resolution is seen clearly towards the end of On repentance:

"In my opinion it is living happily, not, as Antisthenes said, dying happily, that constitutes human felicity. I have made no effort to attach, monstrously, the tail of a philosopher to the head and body of a dissipated man; or that this sickly reminder of my life should disavow and belie its fairest, longest and most complete part. I want to present and show myself uniformly throughout. If I had to live over again, I would live as I have lived. I have neither tears for the past nor fears for the future. And unless I am fooling myself, it has gone about the same way within me as without. It is one of the chief obligations that I have to my fortune that my bodily state has run its course with each thing in due season. I have seen the grass, the flower and the fruit; now I see the dryness - happily, since it is naturally. I bear the ills I have much more easily because they are properly timed, and also because they make me remember more pleasantly the long fidelity of my past life."

He goes on to say that he has no time for these 'casual and painful reformations'. We should learn to live with what we are.

But what about 'real' reform? What about repentance in its religious sense where it means something like a complete turn-around in and of our lives? Montaigne does acknowledge this possibility. For this kind of root-and-branch change, Montaigne makes the following statement:

''God must touch our hearts. Our conscience must reform by itself through the strengthening of our reason, not through the weakening of our appetites. Sensual pleasure is neither pale nor colourless in itself just because we see it through dim and bleary eyes. We should love temperance for itself and out of reverence toward God, who has commanded it... We cannot boast of despising and fighting sensual pleasure, if we do not see or know it, and its charms, its powers, and its most alluring beauty."

|

| 'They spend their days dancing' |

Montaigne's message is by and large strikingly secular in its accents. He seems to be dealing with himself and others in an entirely material world, but this statement seems to go beyond this in an interesting way. For all our ordinary hesitations and hang-ups, our regrets and our attempts at reform, he seems to advocate a sort of wise acceptance of oneself and the limitations of our nature, but we see here that he does accept - even if only glancingly - the more radical possibility of a genuine repentance, something much closer to Christian repentance or metanoia, which reflects the underlying Hebrew concept of teshuvah, which means 'return'. It is an entirely orthodox view that he expresses here. We cannot reform ourselves as though we were engineers of our own natures. For that we need the sort of quality or power that comes from outside ourselves. In traditional theological terms this is the grace or divine gift or favour that comes from God. The opposite view in the theological tradition is what used to be called pelagianism, after the British ascetic Pelagius, whose views were eventually branded as heretical by Augustine at the Council of Carthage. Pelagius thought that you could shape and improve yourself - 'pull your own strings' as they say in California. Augustine took the view that we needed help from outside or above ourselves if we were to have any chance of success in this endeavour.

Two very different views of ethics can be seen here. There is the sergeant-major-cum-schoolmaster view that you can drill and beat people towards perfection and the view that we are not free to become what we ought or want to become and that the power must come from outside ourselves. I think that most of us would want to say that we need something of both these attitudes. We have a certain responsibility for ourselves and can hardly in human terms at least expect to be helped before we have made some attempt to get up on our own feet and that would surely demand a certain amount of habituation, of being brought up in the right way. On the other hand the idea that we can achieve everything by ourselves, as though as each of us were his own Michelangelo, carving beautiful marble versions of ourselves, seems to belie the limitations that we know are ours. Some things are just given, like the gracefulness of a gazelle, and, for Augustine, the gratia or grace of God.

One of the features of modern ethical theory has been a belief that everything can be achieved through human volition and by having the right intellectual view of the world, but as we know that kind of view soon leads to the blind alleys of the police state. The Catholic Church has certainly no better record than the worst of the Jacobins and their modern successors. We need only to think of the Churches behaviour in Spain during the Civil War, but then maybe that was because they too thought that they had all that was necessary for a complete answer to the world's problems, that they had the answer in their hands, like Dostoevsky’s Grand Inquisitor. And Montaigne? Where does he stand in all this? Well, he seems to be almost exclusively concerned with our limitations and contingency and how to come to come to terms with them, and underlying this view, perhaps, is the orthodox Christian view that real reform can only come from outside. As he says at some length in Of experience, you don’t get justice by just making more and more laws. The ingenuity of human reason alone won't get us there, but he isn’t either, as far as I can see, advocating a doctrine of sola fide – the idea that we can be justified in a religious sense by faith alone - much less the enthusiasm of antinomianism. Montaigne isn’t rejecting reason, but he is keenly aware of its imperfect and often self-serving nature. Instead he gently urges an acceptance of our limitations, that’s to say, an acceptance of our contingent nature.

Let me make one last - well, penultimate - observation which perhaps points to a very opposite conclusion. In his essay On cannibals, Montaigne describes the nations of the new world of what was then called New France and which today we know as Brazil:

"These nations then seem to me to be so far barbarous, as having received but very little form and fashion from art and human invention, and consequently to be not much remote from their original simplicity. The laws of nature, however, govern them still, not as yet much vitiated with any mixture of ours: but 'tis in such purity, that I am sometimes troubled we were not sooner acquainted with these people, and that they were not discovered in those better times, when there were men much more able to judge of them than we are. I am sorry that Lycurgus and Plato had no knowledge of them: for to my apprehension, what we now see in those nations, does not only surpass all the pictures with which the poets have adorned the golden age, and all their inventions in feigning a happy state of man, but, moreover, the fancy and even the wish and desire of philosophy itself; so native and so pure a simplicity, as we by experience see to be in them, could never enter into their imagination, nor could they ever believe that human society could have been maintained with so little artifice and human patchwork. I should tell Plato, that it is a nation wherein there is no manner of traffic, no knowledge of letters, no science of numbers, no name of magistrate or political superiority; no use of service, riches or poverty, no contracts, no successions, no dividends, no properties, no employments, but those of leisure, no respect of kindred, but common, no clothing, no agriculture, no metal, no use of corn or wine; the very words that signify lying, treachery, dissimulation, avarice, envy, detraction, pardon, never heard of. How much would he find his imaginary republic short of his perfection? Viri a diis recentes, (i.e., men close to the gods)."

This famous passage appears - or at any rate the last section of it does - as a speech by Gonzalo in Shakespeare's Tempest, where that garrulous old counsellor naively wonders at the perfection of this state of nature. Shakespeare saw through it at once, but many others did not, especially as we move steadily into the secular modern world when this idea of a recoverable primitive perfection started to cast long shadows across the European thought and society. But it is strange to find this passage in Montaigne who usually as we have seen takes such a downbeat view of human possibilities. What was his purpose here? It was partly what it seems to be, praise for the simplicity of a society that seemed to be free of so many of the vices of their French and Portuguese invaders. As with China and later Persia which became at this time images of more rational worlds, so in a reverse but similar way here the newly discovered Indian societies of the Americas become mirrors that reflect back to us images of our distance from a simpler more ‘natural’ world. Montaigne clearly has a very special interest in these people and their world. In this essay On cannibals, Montaigne is also bringing home to us the extent of our hasty and fallible judgement. Their ‘nature’ is superior to our ‘art’, that is to say, to our rational ingenuity. Look at them without prejudice and we will see, he claims, that they have made a much better job of solving the basic problems of society – ways of living together admirably and viably – than Plato managed with his extended account of how to achieve justice or, as he called it, dikaiosune. Montaigne plays with a rhetorical contrast between ‘art’ and ‘nature’ but his purpose is clear – he wants to cast a cold light on our own false opinions and to bring home to us our radical contingency and actual disorder. These images of perfection are mirrors for our own imperfection. His essays as a whole show us that we have to live with our imperfection and not seek to break out of our condition by trying to establish a future perfect world. Many later philosophers were less cautious and took more seriously the idea that we might regain that perfect state of nature glimpsed in distant imaginations, and in trying to construct that more rational society, they authorized ort seemed to authorize terrible excesses. Rousseau is of course the name that comes most readily to mind in this connection. Even today Rousseau has Jacobin successors in figures like the Slovenian philosopher, Slavoj Žižek, who asserts that in order to save the world from the ravages of capitalism we should be prepared to accept a total dictatorship. It is a philosophy that has a certain appeal in the environmental movement.

|

| Slavoj Zizek |

|

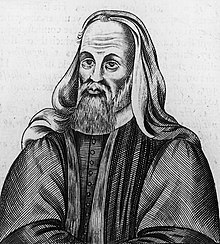

| Pelagius, the British way.. |

One last point: - Is Montaigne philosophy? I think it is, though it is certainly not an academic treatise like those that university academics started to grind out first in late-eighteenth century Germany and then in every other European country. If today we think that philosophy must always be in the shape of abstruse articles or intractable academic treatises maybe we ought to lay the blame at the feet of Immanuel Kant and the university system of the Prussian state. Philosophy wasn't always like that. Plato's essays are highly wrought works of literary art and reflect the changing currents of his thought. The journey was the thinking and the thinking was in good measure (though of course not entirely) about the nature, and how we might attain, good judgment - sophrosune - or as the word ‘philosophy’ itself indicates, the pursuit or love of wisdom, but, as we know, one can chase and chase wisdom but somehow she always seems to get away! Montaigne shows us something about how all this works out in the messy business of living the lives that are given to us.

But maybe you think that we shouldn't give time and space to literary works like Montaigne's Essays? Whatever your view, it is fair to point out that that view of yours, whatever it is, presupposes an assumption about what philosophy is about. Is it intellectual analysis like some of the best things in Aristotle? Or is it about understanding that leads more directly to understanding ourselves and changing our lives? Both views have been present since people started engaging in what they called philosophy, but the second has in the West tended to lose out in recent centuries, although now there is increasing impatience with exclusively academic approaches. So, the implicit question is clear: Why are you doing philosophy? Answers on a postcard, please. One point is perhaps that the more academic variety seeks to influence the politicians and power brokers whereas the other appeals more directly to individuals struggling to make sense of things on their own.

And one last, last note. ‘Pelagius’ is the Greco-Latin name for an ancient Celtic Briton. It means 'man of the sea' and if you translate that back into the Proto-Welsh they spoke here in the fourth century, it comes out as ---- ‘Morgan’! So we have to imagine Augustine having his big set-piece disputation in Rome with Morgan, the Welsh monk!