Euthyphro: Some notes on our meeting...

|

| Rembrandt'sVirgin and Child with cat and snake |

We discussed Euthyphro in specific, bigger and wilder contexts. These notes record some but by no means all of the points mentioned. They do not reflect the order of discussion. Omissions and other comments can be posted in the Comments Box.

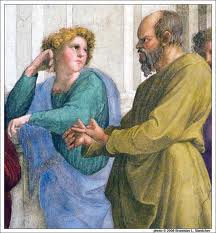

(1) As we can see from Rembrandt's picture of the Virgin and Child with a cat and snake, people and animals have their own ideas about how they should interpret their experience. So why should we regard our perspective as the 'Members Only' door to the truth about the world? This is even more true when one thinks of the differences between one historical era, like Socrates' Athens, and our own world today. This is a text from a world with very different cultural assumptions from our own.

(2) One aspect of those cultural differences was the fifth century intellectual ferment. The Greek world at that time was in disorder, at least in the sense that the world was changing and things were being seen with fresh eyes. This debate covered every aspect of our life in society - about the nature of justice, how we should treat others and educate the young to the best forms of political organisation. These debates were often expressed in terms of the contrast between law or custom or if you like traditional attitudes and practices on the one hand and on the other the natural order as something separate from human values and institutions. For the Greeks this was the contrast between nomos (law, custom, etc) and physis (nature). The word physis is the etymological origin of our word 'physics' and 'physician'. This contrast had been borne in upon the Greeks by their increasing contrasts with the non-Greek world. Other peoples did things differently, so while 'nature' was the same everywhere, people nevertheless held very different ideas about how one should live, that's to say, about what was important in life. This awareness prompted reflections that sought to enquire into the most 'natural' or 'best' way of living, a kind of rational inquiry into the basis of customs, justice and morality. There was a desire to overcome the relativism that seemed endemic as regards people's values.

(3) Herodotus' early story about the Persian ruler Darius: 'During his reign, Darius summoned the Hellenes at his court and asked them how much money they would accept for eating the bodies of their dead fathers. They answered they would not do that for any amount of money. Later Darius summoned some Indians called Kallatiai, who do eat their dead parents. In the presence of the Hellenes, with an interpreter to inform them of what was said, he asked the Indians how much money they would accept to burn the bodies of their dead fathers. They responded with an outcry, ordering him to shut his mouth least he offend the gods. Well then, that is how people think, and so it seems to me that Pindar was right when he said in his poetry that custom is the king of all'. (Histories, 3.38, Robert Strassler's Landmark edition).

|

| It's hard to know what to think when it comes to values. |

(5) Whatever quibbles might be raised about the argument Socrates puts forward about the nature of piety is basically sound and significant. That argument said in effect: Is the holy or what is religiously acceptable what it is because it is loved by the gods, or is it loved just because it is what it is in itself? The effect of this argument is - it was suggested - to take talk about piety and the nature of religious belief and practice out of its normal comfort zone of discourse and to look at it in a new, more detached and secular manner. Logic and rational examination was all that was needed. One did not need, indeed should not take religious language simply on its own terms. One had to break out of this way of talking. It is not difficult to see that this approach might well upset traditionalists in the city, who knew that something was afoot even if they did not know exactly what it was the Socrates was doing. Socrates was himself a deeply religious man. He should not be seen as some sort of early liberal, an agnostic or atheist.

(6) When Socrates says at 14e, 'I prefer nothing, unless it is true', we should probably understand this as a commitment to an ongoing search to sort things out intellectually and that in turn as part of his search for the best way to live. The argument ends up by coming full circle in a contradiction. No conclusion is reached about the nature of the holy or the pious, but some progress has been made simply by opening up the discussion in this way. Euthyphro leaves in dismay and disarray. His claim to expertise has been shown to be an empty claim. We as readers might be tempted to laugh at his discomfiture, but perhaps Plato means us to see that we are really in the same boat as Euthyphro and know nothing for sure or clearly about this issue. The search should go on, but without the Euthyphro's certainties or our self-satisfaction. It is easy to agree with this, but it was also agreed early on that meeting up with Socrates would probably have been a pretty rough experience.

|

| Aporia - being at a loss - isn't always fun! |

We will meet next on 16 November to talk about Plato's Apology. To post comments you may need to sign up as members.