Power and Public Opinion

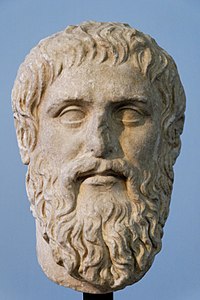

“At the very beginning of Plato’s Republic, when the definition of δικαιοσύνη, justice, is first attempted, an interpretation adumbrated by Cephalus and carried further by Polemarchus is politely but swiftly disposed of by Socrates. It is that right conduct consists in telling the truth and discharging one’s obligations – the hallmark of a true gentleman, as we may also gather from Xenophon’s account of the education of the Persian monarch Cyrus. As amended by Polemarchus, with reference to the poet Simonides, this amounts to rendering every man his due – doing good to your friends, therefore, and harm to your enemies. Socrates discounts this notion by means of a reductio ad absurdam, but it is to be noted that Polemarchus, though bewildered by Socrates’ skill, still clings to his belief. It is after all what he had been brought up on, a sound practical maxim reflecting the norm of civilised society. Guiding everyday actions by a moral doctrine introduced partly to provide a general standard (so that all those among whom the same convention is shared will know how their fellows act and react) and partly to give transient actions a more than transient validity. (See Thucydides I 86). By its means, these actions are related, through the use of value words, to eternal verities – duty, truth, the good, the harmful. It is action to a predictable norm and sanctified by sound moral backing which appeals to the man- in-the-street, and insofar as power is in his hands, or derived from and accountable to him, the action in which it expresses itself must conform to these requirements.

“It is noticeable that in the early Platonic dialogues the first efforts to define the abstract quality selected for discussion always express themselves in terms of action. In the Laches, for example, courage is ‘sticking to one’s post and not runing away’. In the Charmides, sophrosyne, which we have hitherto rendered as ‘restraint’m or ‘moderation’, is expressed as ‘to do everything in an orderly manner without fuss, like walking along the street and talking and everything else’. The man-in-the-street needs to have a moral reason and justification for doing what in fact he does do, even though he may not profess any high standard of morality, or indeed any morality based on metaphysical or religious conviction; and he will feel this need even though the actions themselves possess no inherent moral content. The concept of power, which has been the theme of these investigations, falls into this category; in itself, it has been evisaged as independent of morality. But that is not the attitude towards it which is generally accepted and generally by harming our adversaries who arouse feelings of apprehension in uspoints must first be made. The first is, that its proper use follows almost exactly Polemarchus’ definition of justice; the popular attitude to power is that you use it to help your friends and do down your enemies, and that in so doing its use must be endorsed by the term ‘just’. The second point – and one which has been postulated at earlier stages of the discussion – is that power is popularly held to express itself in positive action, in achieving the individual end that you want to achieve.

“On this second matter the quotation from Jules Feiffer, which precedes this chapter, is eloquent enough. The definition is of that Platonic kind we have just looked at – ‘power is chasing off the rival and getting the girl’. [Or in substitute cartoon I have used – ‘power is undermining the male ego and getting your man]. It is evident that to the ordinary man, charity very properly begins at home, and number one comes first. Plato’s analogy in the Republic between the microcosm of the individual man and the marcocosm of the polis is exact, in that states operate thie policies on the same premises as those on which the individual citizen operates his. The principal use of power is promote our own advantage, ὠφελία, and our honour, status or dignity, τιμή, by helping our friends and among them our best friend, ego; and it is further used to ward off apprehension, δέος, who arouse feelings of apprehension in us.To this extent, theerfore, the evidence of Thucydides which we have considered in this connexion accurately produces what we may judge to have been the current, everyday approach to communal or individual actionalys. Where we run into difficulty is that Thucydides in his is analysis of the matter is strict in discounting the basic validity of our first point – that you use it , to help or to harm, in a manner ergarded as ‘just’. To him all arguments revolve, when the cards are on the table, around the requirements of expediency and advantage, and we have see that this is a fair assessment since the power intending to achieve these things is not in itself concerned with any other aspect of the matter. Nevertheless there remains a need for spititual or moral support, a need to say that an action is ‘right’, that a decision is ‘equitable’, that shares are ‘fair’, that a war is ‘just’ or even ‘holy’, that an inquisition is ad maiorem Dei gloriam, that chicanery, slaughter, destruction are carried out for ends which are in themselves ‘good’ on an absolute standard (thus of course ‘justifying’ the means) and which bring benefit to their victims eve though the victims may not, at least in this world, be able to testify to the accuracy of this appraisal. You can make a desert, as Tacitus later observed, and call it ‘peace’; you can give it, indeed, any name you like, and it will be valid for you with all its overtones. Whatever the Realpolitik behind the action, the necessity of giving it a respectable nomenclature cannot be gainsaid.”

Ω

On this view as expressed here by Geoffrey Woodhead can there be any absolute moral standards?

.jpg/400px-James_Anthony_Froude_(Waddy,_1872).jpg)