Thucydides' History of the Peloponnesian War

|

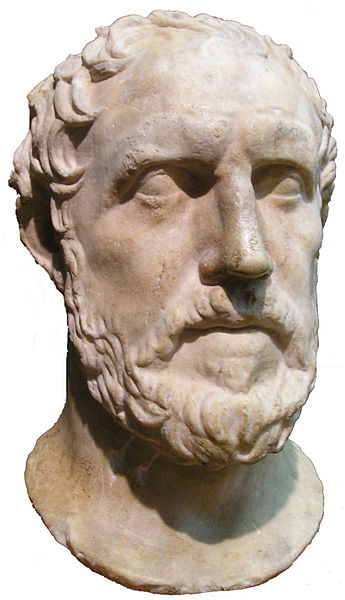

| Thucydides, 460 - ca.395 BC |

Thucydides' claim was no empty boast. His historical analysis surveys the Greek world at a time when war was putting every notion of what civilized life was about under intolerable stress. War is, he said, a violent teacher. He meant this perhaps not only in its obvious first-line meaning but also in the sense that it revealed the nature and character of human life and society. War was the acid that revealed the outlines of human nature. Thucydides' great achievement was to give us a complete conceptual picture of the world and how it warps under the pressures of war. This is analytical philosophy long before the term was invented and it is this that we should be looking for as we read, keeping track of the way he uses key terms in his extended diagnosis. Later, his outline was taken up and must have had a considerable influence on the young Plato's analysis of the decay of states from an imagined ideal through a spectrum of political forms - aristocracy, timocracy, oligarchy, democracy and finally tyranny - but where Plato is abstract, didactic and schematic, Thucydides is vivid, factual and deeply moving. He is free from the imposed patterns of his younger contemporary, but he has clear and somewhat conservative and aristocratic sympathies.

At the risk of considerable distortion, I will try to outline some of the most important concepts in his analysis. Perhaps least apparent is his conception of what it is to be civilized and properly human, the ideal in other words that guides his view of all these violent departures. Lying at the root is the distinction between νόμος and φύσις. The first, νόμος or nomos means more than law or convention. It signifies the values of civilisation, the things that mark human beings at their best as separate from the unbridled anarchy of φύσις or nature. Nomos is for Greek writers and poets 'divine nomos', divine in the sense that it is the stable cosmic order instituted by the gods. It is the fragile expression of a civilized life that is all too easily threatened. Such a person has a certain nobility of character - τὸ γενναῖον - which shows itself as openness, even simplicity - εὐήθης - a lack of suspicion about the motives of others. His kind of openness can only flourish in stable situations where people can readily believe what others say. A noble character has a kind of unreflective confidence in himself and his outlook. It is of course a picture of the aristocratic temperament and as such one liable to attack in a rougher world. For Thucydides, as for all Greeks, the happiness of individuals and the stability of the state is always under threat from the accidents and blows of fortune. They never forgot the radical contingency of our lives. This went under the general name of τύχη. τύχη is what one obtains - τυγχάνει - from the gods, good fortune, luck, but also bad luck and misfortune. To be born a slave or taken into slavery was the supreme misfortune. It is the way things fall out. The two most destructive forms of fortune are war and disease. We see in the plague in Athens (following ironically hard upon Pericles' speech praising the city as the supreme expression of civilisation) and in the consequences of war.

Man's difficulties are of course also very largely man-made and no métier is more supremely human than war. Nothing undoes human nature and human society quite like war and especially civil war. Thucydides shows us the terrible effects of the civil war in Corcyra (Corfu). We see how war leads to the dissolution of all norms, laws and forms of respect, everything that for the Greeks was summed up in the word εὺσέβεια which means more than just reverence or piety towards the gods. He shows us how people start to use words in new and often dishonest or self-deceived ways and how lies and every form of fraud becomes the praised norm. For him the worst condition for a society was stasis or civil strife. It leads people into partisanship, dishonest appreciation of others' arguments and contentions and generally the destruction of civilized behaviour. He also shows us the pursuit of power has its own inescapable 'logic' that drags people lower and lower. Few things are more horrific than the debates over Mitylene and Melos. The shame that keeps men from behaving in bad ways and exhorts them to live up to better images of themselves comes to be regarded as foolishness. People no longer have the same self-images for their lives.

One further contrast could be mentioned here. It is one that was central to the fifth-century intelectual debate – that between τύχη and τέκνη; that is to say, between the radically contingent nature of the world and technology, for technology is our basic answer to life’s uncertainties. It enables us to overcome the worst aspects of the world that threaten human survival. But this human inventiveness also leads us (it might be argued) to become ‘overreachers’ in a more general sense, dedicating our lives to the pursuit of power over others without any of the restraints imposed by traditional norms and values. It is hard not to see something of our modern situation in this criticism. Once we go down that road and we are far down it – it brings its own irreversible ‘logic’, the necessity or ἀνάγκη that Thucydides talks about so often. The drive to satisfy our hunger becomes our unquenchable greed for power over the world and everything and everyone in it. But maybe you see things in a more optimistic light...

I leave these questions for you to think about over Christmas. I do hope that you will find Thucydides interesting enough to read every golden word in Paul Woodruff’s selection. It’s certainly worth the effort.

| A tenth-century manuscript of Thucydides' History |

No comments:

Post a Comment