|

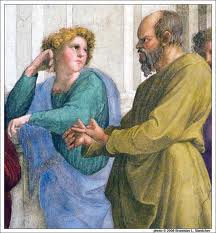

| Socrates talking to the young Xenophon |

Commentators usually talk about Socrates' irony or even the Socratic method. Socrates does adopt an ironical attitude to his interlocutors, such as Euthyphro. To some extent it is the characters he invents who invite this attitude towards themselves. They usually have one thing in common: they assume that they know something or are experts in some area or other, like Euthyphro on piety, or the generals Nicias and Laches on courage, or Charmides and Crito who later show themselves to be overreaching tyrants who discuss temperance or self-control (sophrosune). These people are not just ignorant for they claim to know about these topics. This stance brings down on them the innocent but insistent questions that ultimately reveal their ignorance. If Plato's dialogues were nothing more but pictures of the dialectical rout of the overweening and arrogant, then they would be little better than intellectual Punch and Judy shows, satisfying demonstrations of presumptio brought low, but there is something more than that going on in these dialogues. Perhaps the best way to bring this out is by quoting at some length from Alexander Nehemas' book The Art of Living: Socratic Reflections from Plato to Foucauld.(UCP, 1998) which makes this point much better than anyone else could:

|

| Let me tell you about piety... |

"Given Euthyphro's character, it is natural for us, as the dialogue's imaginary audience, to believe that he could have missed Socrates' point so completely. How could he have seen it, given how dull, how ignorant, and how self-satisfied he is? Euthyphro's personality explains why Socrates fails to have any effect on him. And that in turn explains why Plato chose to compose his dialogue around him. Despite all Socrates' efforts, Euthyphros's supreme self-confidence allows him to remain quite unshaken in his conviction that his legal action is correct and that no one can match his knowledge of the gods' desires.

"But we know better. We can see through this self-deception. We look on as Euthyphro, blind in his self-assurance, misses Socrates' point again and again, and we manage to avoid the traps into which he falls. We realise, as generations of Plato's readers have realised, that self-delusion of the kind Euthyphro manifests is Socrates' greatest enemy. Detecting self-deception in others is not such a difficult things to do, after all; as Lionel trilling remarked, the 'deception we understand and most willingly give our attention to is that which a person works upon himself.' And we are not like this grotesquely silly, conceited, and inane man: how could we be like this gross caricature, whose only reason for being is simply to misunderstand what Socrates believes? But we understad; we are on Socrates' side; we know better.

"And knowing better, what do we do? Mostly, we read this little dialogue and then we close the book, in a gesture that is an exact replica of Euthyphro's sudden remembering of the appointment that ends his conversation with Socrates. We too go about our usual business, just as he proposes to do. ASnd our usual business does not usually center on becoming conscious of and fighting against the self-delusion that characterizes Euthyphro and that, as we turn away from the dialogue, we demonstyarte to be ruling our own lives as well whcih is really the aim of this whole mechanism. Socrates' irony is directed at Euthyphro only as a means; its real goal is the reader."

|

| Seeing Euthyphro discomfited we too leave feeling rather smug. |

Philosophy as a way of life

This raises a question about the status of the elenchus, that is to say about the tough logical argument that is usually taken to be the kernel of the dialogue. People often take this as the 'real' message of the dialogue and treat everything else as just frippery, like lace on the back of a sofa. I hope that enough has been said to suggest that this would be a serious misreading of Plato's Euthypthro. Plato has Socrates knock Euthyphro about a bit, in terms of argumentation that is, and since Euthyphro is such a prig we don't really mind his being beaten up a little. 'Serves him right', we are tempted to say, but our reaction is part of Plato's elephant trap with us, the readers, as the elephants; for behind Socrates' irony is Plato's irony who leads us into the temptation that we are most likely to fall victim to, that of not seeing ourselves with the same hard-edged clarity as we see others, like Euthyphro. We see ourselves as different from him, ironically because we are rather like him.

Here are two more paragraphs from Nehamas' book that talk about this aspect of things: "The close study of Plato's texts is mostly a logical exercise; its apparent dryness may disappoint those who expect more of philosophy. But when it comes to justice, wisdom, courage, or temperance - when it comes to the virtues that were Socrates' central concern - our beliefs about them are central to our whole life, to who we are. To examine the logical consistency of those beliefs, when undertaken correctly, is to examine and mold the shape of the self. It is personal, hard exercise, a whole mode of life ... The logical examination of belief is a part - but only a part - of the examined life.

"The dialogues ask their readers, as Socrates asks Euthyphro, to make their life harmonize with their views. Is there, as Plato's Socrates seems to think, a consistent set of beliefs in accordance with which a life can be lived? Can we have the harmony he is after? I am not sure. And even if we can, I am almost certain that there isn't a single set of beliefs that supports a single mode of life that is good for everyone. But that is not the issue that faces us here. That issue in (Michael) Frede's words... is that 'to know.. is not just a matter of having an argument, however good it might be, for a thesis. Knowledge also involves that the rest of one's beliefs, and hence at least in some cases, one's whole life, be in line with one's argument ... In this way, knowledge, or at least a certain kind of knowledge Plato is interested in, is a highly personal kind of achievement.' Philosophy is not here only a matter of reading books: it is a whole way of life, even if, as I believe, it does not dictate a single manner of living that all should follow."

Questions

(1) What do you think? Do you agree with Frede and Nehamas or with Socrates and Plato?

(2) In the Euthyphro, does Socrates already know what piety is? Is he just pretending that he does not know so that his interlocutors will endeavour to discover it for themselves? Or is his ignorance genuine?

(3) If he already knows the answer as regards the nature of piety, then isn't his irony simply a pedagogic method, a way of reaching dumb and unmotivated students? His irony is on this reading simply a kind of didacticism, a way of teaching something that is already known.

(4) If his ignorance is genuine, then what is his irony all about? What is its relation to the evidently exemplary life he led?

(5) What is irony? What is the meaning of this word we use so easily and unthinkingly?

No comments:

Post a Comment