| ||

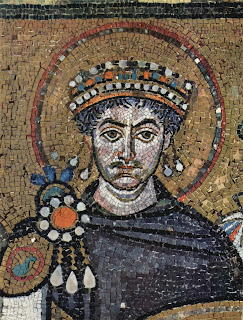

| Justinian closed Plato's Academy in 529 AD |

Plato's doubts about the human condition may be well-founded, but in terms of the philosophical theory he builds upon this conviction, he has rather loaded the dice; for in the Allegory of the Cave, Plato claims that what we are seeing as we stare at the images on the back of the cave are the shadows of those real things which we do not and cannot see in terms of the story he presents. The imagery implies not just that our view of the world is wrong-headed in every way, but also that there is a single, right and true way of viewing the world. Each of us has his own mistaken and skewed view of the world, but there is implicitly in the way Plato presents his picture, a one, true right way to understand things and he holds out the hope that we might by examining our lives bring what we know and what we are closer together. Well, maybe, might be our answer. One thing is certain and that is that our beliefs about ourselves and the world are in something of a mess. We feel instinctively that this is true. We are always trying to get to see the world and ourselves aright. And Plato would certainly agree with this.

|

| How would you be different if you got out there? |

Shadows get a bad press and always have had even before Plato. We are afraid of the shadows because we don't know who or what may be lurking there. The darkness is a place of threats. The real world is a place of danger and we are vulnerable creatures. Once we are away from the security of our homes and away from the city lights it doesn't take much to awaken our elemental fears of the world around us. Hoodlums and rapists, bacteria and crocodiles, unshaven policemen and airplanes falling out of the sky people our imaginations and the books we take on holiday to the beach. Perhaps part of the reason our beliefs and understanding are in such a mess is that we are such vulnerable creatures. We are constantly on the lookout for things that might threaten our lives. We take our inner Darwin with us everywhere.

Of course we have ways of dealing with these threats. We have policemen and judges and gaols and armies to protect us from some of the most present dangers that come from others of our kind. The search to make these defences cast-iron-strong continues month by month in our courts and parliaments. And we have much older technologies to protect us from the threats to our survival - housebuilding skills, agriculture instead of relying on what we find the way worms and birds do, shipbuilding and navigation to help us to get hold of the sort of goods that will enhance our lives with things we don't have in our own country. The list is endless as a moment's reflection will convince you and all of these things are prompted ultimately by our search for safety and survival. They are our answers to our vulnerability. We are easily damaged creatures. The fear of death is never very far from our minds.

But let's look for a moment in a more dispassionate way at shadows, the real shadows that are an integral part of the world. You do not need a brightly shining sun to get shadows. Shadows are everywhere all the time as long at least as there is some light. In fact the only times there are no shadows are when the world is either completely dark or when it is completely white with light. We are either plunged into fearful darkness or immobilised by blinding unintelligible light. (It's surely not an accident that the first is the traditional image of Hell and the other of Heaven). The world only makes visual sense in between these extremes.

The strange thing about the digital image above is not just that some parts look like solid protruding spheres and others like hollow concave bowls; it's also the fact that if you turn the image upside down, the two sorts of images change places. In fact these two images are one and the same: it is the shadow effect that leads us to see them differently. Shadow is ambiguous and requires the interpreting mind. According to Diogenes Laertius, Heraclitus (550-480BC) claimed that celestial bodies are bowls with their concave sides towards us and that in this concavity they hold a flame whose light streams down to people on earth. It's easy to mistake one shape for the other. The point however remains - it is the shadows that lead us to make inferences about objects or rather it is the mixture of shadows and light that gives us clues as to what we are seeing. Sometimes, in some tricky situations, we might have to conduct a few checks to discover how things really stand in the world. Everyday life is just the same, only murkier and less easy to ascertain in the time available to us. Imagine looking at the dense thicket. A slight movement might mean a breeze or it might mean a predator bearing down on us. We have to make the right interpretation and make it fast.

What's the point of all this? Well, the point is, I think, that our judgements about things out there in the world are uncertain. Sure, we have ways of checking up to see if we got it right. We can do astronomy for a couple of thousand years and then feel fairly confident that we understand the basics about celestial bodies and we can walk into the forest to see if it really is a leopard waiting there for us in the branches. But even though we feel that we've got things right we know that we must remain aware that we might be getting them wrong, and that this could be shown to us either now or in the future. There are no ultimate certainties, but experience, science and technology make us feel less fear when faced with threats to our lives. We feel that someone can do something to fix it, whatever 'it' is - a triple by-pass operation or the failure of fish stocks in the seas. Plato, however, did want to assert that there are certainties, that we could know the world and our own characters and qualities. He started with the idea of real objects that the dull souls in the back of the cave - hoi polloi - just didn't quite see. They saw only the shadows of those real things. Those real things were the constituents of the intelligible world and were somehow more real than the imperfectly edited torrent of experience, which is what passes for life in the lives of us ordinary cave-dwelling folk. Today, people for the most part reject Plato's notion of an impersonal Good towards which we all should aim, but on the other had, we have almost unlimited confidence in science and technology, in what Plato saw as just a set of ad hoc technai and procedures that help to protect and enhance our lives. We tend to think that everything is ultimately just a matter of medical or some other kind of engineering.

|

| "...an appendage without influence..." |

Plato may think little of our average attempts to make sense of our lives, but he does believe that this is a real possibility and that a noble destiny awaits the supreme philosopher, that lover of wisdom who ventures out beyond the cave and into the light of ultimate reality. (It is no wonder that Nietzsche called Christianity Platonism for the masses!) Montaigne takes a very different view. Here is how Hugo Friedrich characterizes Montaigne: 'One can open the Essais at any random passage, they are always concerned with man: "...the study I am making, the subject of which is man..(II,17, 481 A). Montaigne stresses his predominant theme in this and similar wording often and almost extraneously. Whether nature, being or God is discussed, it is always for the purposes of characterizing man. These are forces to which man must submit, dark areas over which the fantasy lights of human opinion play, restlessly and incompetently. And this book, which displays all moral, physical, political, intimate characteristics of man like an inexhaustible landscape, pushes him all the way to the edge of the cosmos: an appendage without influence, uncertain in his sense of rank, unclear in his driving forces, incalculable in his reactions to destiny, much more likely to be related to the animal than to the divine, and then again capable of finding happiness and peace in the midst of his ignorance and abasement, creating the art of social intercourse, attaining the summit of friendship, poor and rich alike, a surprise with which one never fully comes to terms - "so deep a labyrinth..." (II, 17 481 A).' (Montaigne, by Hugo Friedrich, UCP, 1991).

There is nothing in the Essais of the Christian doctrine of man's esential dignity. The Christian concept of a conditio humana gives way to a recognition of our confused all-too-human condition. His picture of man acknowledges no robed destinies for kings or parliamentarians or peasants. We are all the same, riding the uncertain waves of experience, buffeted this way and that. The emperor and the shoemaker are cast in the same mold, their lives not all that different from each other. A prince waging war or a neighbour negotiating privately with a neighbour, beating a servant in one's household or ravaging a province: do not these stem from one and the same root? (II, 12, 350 A). We are all subject to the same accidents. It was Shakespeare - a very keen student of Montaigne - who with his History plays brought this notion of the common humanity of kings and peasants vividly before his Elisabethan audiences. (One might think for example of the scene where the young Henry V tours the English camp on the night before the battle of Agincourt talking anonymously to the ordinary soldiers or of Hamlet's rebuke to Claudius where he tells him 'how a king may go a progress through the guts of a beggar', reminding the king of our common nature in an abrupt and brutal manner). Our limitations are more real than our pretences, but on the other hand, our common humanity is something to be affirmed. Montaigne's essential scepticism about higher destinies and the like leads him not to despair but towards affirmation of our imperfect nature and from there towards advocating toleration in what was a dangerously intolerant age.

CLOV: Do you believe in life to come?

HAMM: Mine was always that.

Lines from Samuel Beckett's Endgame